Kumbh Mela: how a superspreader festival seeded Covid across India | India

On 12 April, as India registered another 169,000 new Covid-19 cases to overtake Brazil as the second-worst hit country, three million people gathered on the shores of the Ganges.

They were there, in the ancient city of Haridwar in the state of Uttarakhand, to take a ritual dip in the holy river. The bodies, squashed together in a pack of devotion and religious fervour, paid no visible heed to Covid protocols.

This was one of the holiest days of the Kumbh Mela, a festival that has become a highlight of the Hindu religious calendar and is known for drawing millions of pilgrims, seers, priests and tourists.

In the weeks beforehand, as a deadly coronavirus second wave began engulfing India, anxious calls to cancel the festival were rebuffed by the state and central government, which are both ruled by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata party (BJP). On 21 March, a full page newspaper advert featuring the prime minister, Narendra Modi, invited devotees to the festival, assuring them it was “clean” and “safe”.

But as festivities got into full swing in March, testing capacity was criticised as inadequate. Masks, though mandatory, were largely absent. The Uttarakhand BJP chief minister, Tirath Singh Rawat, who had earlier told devotees that “faith in God will overcome the fear of the virus”, was among the millions pictured taking part in the rituals wearing no face covering. Police overseeing the event said that were they to enforce social distancing, “a stampede-like situation may arise”.

By 15 March, more than 2,000 festivalgoers had already tested positive for Covid-19. Two days later, Modi backtracked and called for the Kumbh Mela to be “symbolic”, but it was too late. By the time the festival ended, on 28 April, more than 9 million people had attended.

The true toll of the Kumbh Mela will never be known, due in part to an alleged effort to stop collecting data. Thousands of pilgrims returned home without having been tested or quarantined and without any track of them kept by the government.

Some states began a belated effort to trace and quarantine the returned. In Madhya Pradesh, 789 pilgrims were traced from eight districts and 118 tested positive.

But as media attention focused on Covid-19 cases among the Kumbh returnees, the officials were ordered to stop counting. Four officials in different districts of Madhya Pradesh, as well as officials in Rajasthan, confirmed to the Guardian that their seniors called them off for political reasons.

“We were told to concentrate on the general Covid situation, and not focus on surveys and tracing of Kumbh pilgrims,” said a senior district official in Rajasthan, who requested anonymity, fearing reprisal.

Accounts gathered by the Guardian from the states of Uttarakhand, Madya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Kashmir and Karnataka indicate that the virus travelled back with countless devotees and found its way to poor rural communities where access to healthcare and testing was limited or absent, with often devastating consequences. “Pilgrims from all states carried variant viruses and seeded epidemics,” said T Jacob John, a former director of virology at the Indian Council of Medical Research.

In the aftermath, Ashish Jha, dean of the School of Public Health at Brown University, said the Kumbh Mela was possibly “the biggest superspreader event in the history of the pandemic”.

The government has stood by its decision to hold the festival. The BJP vice-president, Baijayant Panda, said “ignorance” and “hinduphobic elements” were behind it being labelled a superspreader event.

Nonetheless, in the week that followed the festival, the host state of Uttarakhand registered a 1,800% increase in Covid cases, many of which have been linked in some way to the festival.

The stories of the returnees provide a snapshot of the Kumbh Mela aftermath.

Kashmir: The Politician

Thakur Puran Singh, 79, a BJP leader and former minister in Kashmir, refused to the end to believe that he had caught Covid-19 at the Kumbh Mela.

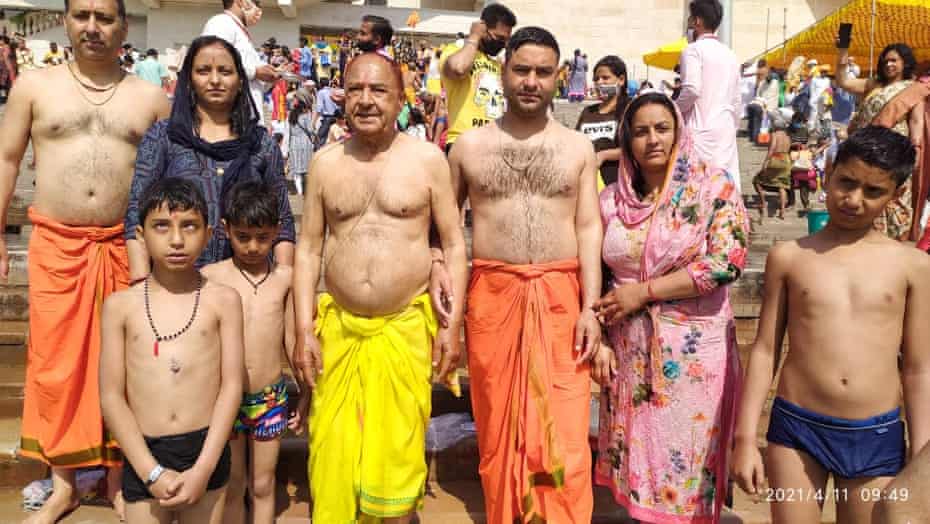

At the crack of dawn on 9 April, Singh and his extended family, including his two sons, their wives and three grandchildren, piled into two escorted SUVs and drove 370 miles to Haridwar. They reached the Kumbh Mela by the afternoon. For the next five days, the family took multiple dips in the Ganges.

On 16 April, the day after returning, Singh began to experience symptoms. He dismissed them at first, but by 21 April his condition had deteriorated. His son, Dinesh Singh Thakur, took him to a local hospital, where doctors suspected Covid due to his damaged lungs. Thakur wanted a second opinion, and embarked on a journey to take his father to another hospital he believed was better.

“I could not believe the doctors and their Covid theory. I did not even put on a mask while driving my father,” said Thakur.

But Singh died on the way. Eight days later, his elder brother Balwant Singh, who the family had seen on their return from Kumbh, also died – again with symptoms suggesting complications caused by Covid.

“Even after Singh’s death, the family concealed that they had travelled to Kumbh,” said Dr Shameema, chief medical officer of the district. Dr Iqbal Malik, another health official, confirmed that four members of the family had tested positive.

A test-and-trace official said more than two dozen people contracted the virus after contact with Singh’s family members, who had attended four weddings after Kumbh Mela.

“These are the cases we have been able to track, but it is highly likely that the number is much higher,” the official said, again on condition of anonymity.

Singh’s body was cremated as per Covid-19 protocols, but his family still believes the virus didn’t kill him. “Why did only my father die when we were 11 members there?” said Thakur. “It is not a virus which kills. The death is destined. I have no regrets.”

Madhya Pradesh: The farmer

Gopal Singh’s family and neighbours were thrilled to see him return home from Kumbh Mela. The people of Madhi Chaubisa village, in Madhya Pradesh’s Vidisha district, came out to receive him and to get ashirwad blessings, with the young customarily touching his feet. But the 56-year-old farmer was filled with dread.

Singh had joined around 100 other people from the surrounding villages who boarded two buses and embarked on a holy pilgrimage to Kumbh Mela. While there he saw people falling sick, and on the way home many of the bus passengers complained of high fever and diarrhoea. But they were not stopped anywhere for Covid tests, said Singh, nor for temperature checks.

“I have been to Kumbh twice before, but I have never seen anything like this – so many people getting sick,” he said.

Singh insisted on a Covid-19 test on his return, despite a local doctor dismissing his concerns. Four days later it came back as he feared: positive. In the meantime, he had mingled with many of the villagers.

Three more Kumbh Mela returnees soon tested positive in his village, then more in the surrounding villages. “After people came back from Kumbh, cases increased to over 30 in just a few days,” said Ragu Raj Dangi, 32, the head of the village. “And many people who had symptoms and those who came in contact of Covid patients were not getting tested.”

A few days later, Singh’s neighbour Mamta Bhai, 40, a mother of two children, developed a fever. For several days she was treated by a local doctor, but when her oxygen levels dipped to critical levels she was taken to an ICU. She died.

Singh said he is filled with guilt. “Our stubbornness and superstitious belief has bought us a catastrophe,” he said. “I am feeling very weak, and more than that I am feeling bad about those people who might have contracted the virus because of people like me.”

Uttar Pradesh: The Holy Man

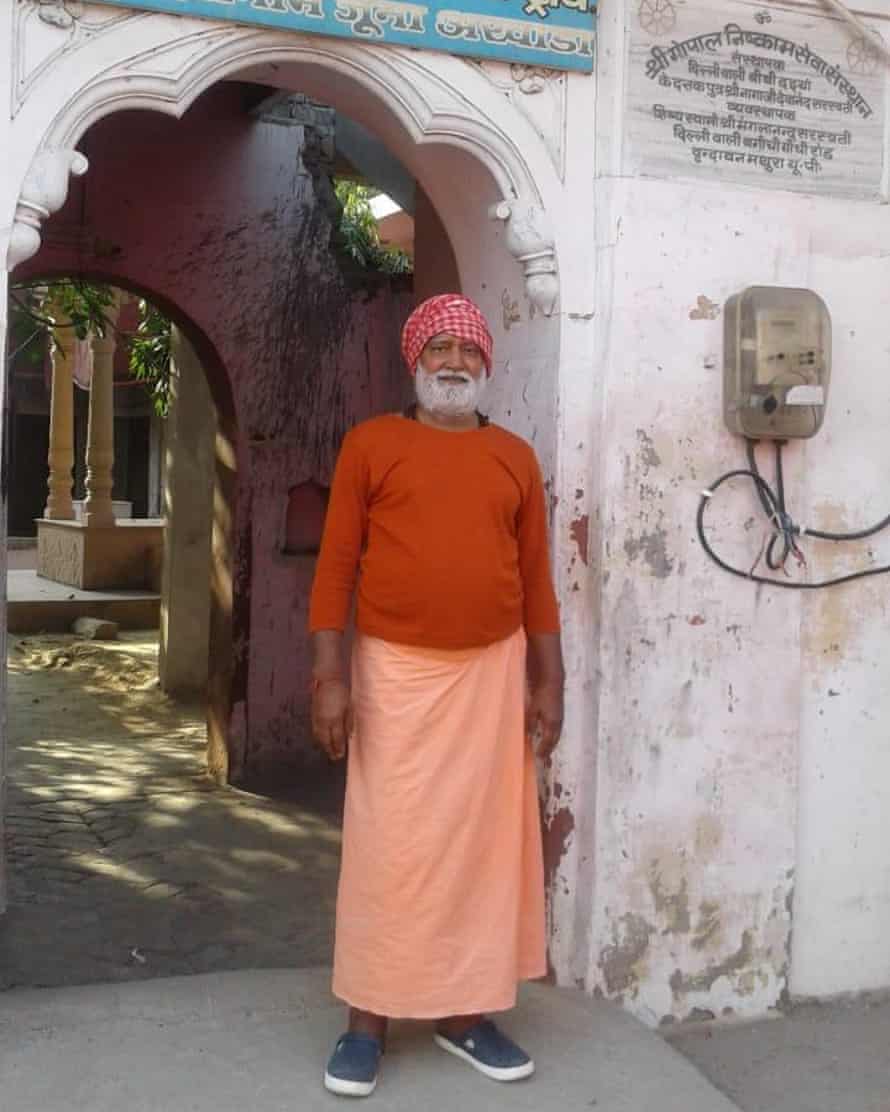

As a high priest in one of India’s largest Hindu monasteries, there was never any question of the 74-year-old Pragyaanant Giri staying away from the Kumbh Mela. Like many at his ashram – Juna Akhara, in the town of Vrindawan, Uttar Pradesh – he believed coronavirus to be a conspiracy.

But after spending a month at the festival, Giri – a former policemen turned priest – developed a sore throat and fever. His fellow holy men recommended he take some time off, so he went home to the ashram. But his condition deteriorated, and he was taken to a hospital, where he tested positive for Covid-19. After two weeks in the intensive care unit, Giri died. In defiance of Covid protocols, his body was taken back to the ashram and buried.

People in the ashram described how cases shot up when Giri returned. “More than a dozen people who came in contact with him developed Covid-19 symptoms, and some had to be hospitalised,” said one. “But most of them never got tested.”

Yet even after Giri’s death, the prevalent belief in the ashram was that Covid was not real. Swami Harigiri, the head of the ashram, said it was a conspiracy against Hindus to call Kumbh Mela a superspreader event.

“We drink cow urine,” he said. “[Coronavirus] will not affect us.” Giri’s death being attributed to Covid-19, he said, was “fake news”.

Bihar: The pious women

Before Kumbh Mela the small village of Brindaban in the eastern Indian state of Bihar had been relatively unscathed by the pandemic. On 6 April a group of five women left for the festival on an 11-day trip. Days after their return, two were dead.

Although the local health department claims the victims had tested negative for Covid after death, their family members tell a different story.

“She fell sick the day she returned home, and the very next day she died,” said Awadh Kishore Tiwari, a nephew of Bindu Devi, one of the two women who died. Devi, who was 70, had a cough and a fever, said Tiwari. He added that his own mother, who was otherwise housebound, tested positive for the virus after meeting Devi.

Her death triggered a wave of panic. Forty villagers were tested and the whole village was sanitised and declared a containment zone. The local chief medical officer, Avinash Kumar, said only one of the pilgrims had tested positive for Covid-19 but conceded that his officials used only rapid antigen tests, which have a high rate of false negatives.

Bindu Devi’s death was followed closely by that of fellow pilgrim Dulari Devi. Relatives said the 58-year-old developed breathing problems the moment she returned from Kumbh Mela.

Her brother-in-law Awadhesh Chauhan said he had advised her not to attend Kumbh Mela because of Covid, but the pious woman had laughed it off. “She told me that nothing will happen to her, you need not worry,” he said.

Karnataka: The psychiatrist

When a 67-year-old woman from Nandini Layout, a suburb of Bengaluru, tested positive for Covid days after returning from the Kumbh Mela, her family grew frantic.

Living in the house with her was her daughter-in-law, a psychiatrist who worked in a hospital where she saw dozens of patients. Tests soon confirmed she too had Covid. Testing teams rushed to the hospital. “We found 12 patients and three staffers Covid-19 positive,” said Dr Manjala, who headed the team.

Eighteen other close contacts of the woman were eventually diagnosed with Covid, but officials said the true spread of the virus was likely to be even greater.

Everyone traced to the woman has recovered, but the family said they now feel unjustly stigmatised. “We cannot be blamed for this,” said the psychiatrist, who does not want to be identified. “It is the government that holds responsibility for allowing such a religious gathering.”

Manoj Chaurasia contributed reporting from Bihar

The post Kumbh Mela: how a superspreader festival seeded Covid across India | India appeared first on Chop News.

from Chop News https://ift.tt/3wW1MpZ

Post a Comment